Measuring User Perceived Performance to Prioritize Product Work

/I’m excited to announce that my colleague Heather McGaw and I will be speaking at Performance Matters (#PerfMatters) this April.

Read MoreI’m excited to announce that my colleague Heather McGaw and I will be speaking at Performance Matters (#PerfMatters) this April.

Read MoreIn his 2015 novel, Satin Island, Tom McCarthy’s protagonist (known only as “U”) is a corporate anthropologist working for an outre design research firm whose work embodies all the absurd contradictions of late capitalism. The highly influential firm’s logo is “a giant, crumbling tower.” The visionary owner and boss of U takes pride in telling his clients that he is selling them “fiction” and in talks to Davos-like conferences speaks primarily in Nietzschean aphorisms. Ultimately, McCarthy portrays the role of his protagonist and design researcher as the ideal specimen of the late capitalist job.

Read MoreLike many organizations, Mozilla Firefox has been experimenting with the Google Ventures Design Sprint method as one way to quickly align teams and explore product ideas. Last fall I had the opportunity to facilitate a design sprint for our New Mobile Experiences team to explore new ways of connecting people to the mobile web. Our team had a productive week and you can read more about our experience in this post on the Sprint Stories website.

Read MoreLast year, the Firefox User Research team conducted a series of formative research projects studying multi-device task continuity. While these previous studies broadly investigated types of task flows and strategies for continuity across devices, they did not focus on the functionality, usability, or user goals behind these specific workflows.

For most users, interaction with browsers can be viewed as a series of specific, repeatable workflows. Within the the idea of a “workflow” is the theory of “flow.” Flow has been defined as:

a state of mind experienced by people who are deeply involved in an activity. For example, sometimes while surfing the Net, people become so focused on their pursuit that they lose track of time and temporarily forget about their surroundings and usual concerns…Flow has been described as an intrinsically enjoyable experience.¹

As new features and service integrations are introduced to existing products, there is a risk that unarticulated assumptions about usage context and user mental models can create obstacles for our users. Our goal for this research was to identify these obstacles and gain a detailed understanding of the behaviors, motivations, and strategies behind current browser-based user workflows and related device or app-based workflows. We will use these insights to develop products, services, and features for our users.

In order to understand users’ workflows, we employed a three-part, mixed method approach.

Survey

The first phase of our study was a twenty question survey deployed to 1,000 respondents in Germany provided by SSI’s standard international general population panel. We asked participants to select the Internet activities they had engaged in in the previous week. Participants were also asked questions about their browser usage on multiple devices as well as perceptions of privacy. We modeled this survey off of Pew Research Center’s “The Internet and Daily Life” study.

Experience Sampling

In the second phase, a separate group of 26 German participants were recruited from four major German cities: Cologne, Hamburg, Munich, and Leipzig. These participants represented a diverse range of demographic groups and half of the participants used Firefox as their primary browser on at least one of their devices. Participants were asked to download a mobile app called Paco. Paco cued participants up to seven times daily asking them about their current Internet activities, the context for it, and their mental state while completing it.

In-Person Interviews

In the final phase of the study, we selected 11 of the participants from the Experience Sampling segment from Hamburg, Munich, and Leipzig. Over the course of 3 weeks, we visited these participants in their homes and conducted 90 minute interview and observation sessions. Based on the survey results and experience sampling observations, we explored a small set of participants’ workflows in detail.

Product Managers participating in affinity diagramming in the Mozilla Toronto office

Field Team Participation

The Firefox User Research team believes it is important to involve a wide variety of staff members in the experience of in-context research and analysis activities. Members of the Firefox product management and UX design teams accompanied the research team for these in-home interviews in Germany. After the interviews, the whole team met in Toronto for a week to absorb and analyze the data collected from the three segments. The results presented here are based on the analysis provided by the team.

Based on our research, we define a workflow as a habitual frequently employed set of discrete steps that users build into a larger activity. Users employ the tools at hand with which they are familiar (e.g., tabs, bookmarks, screenshots) to achieve a goal. Workflows can also span across multiple devices, range from simple to technically sophisticated, exist across noncontinuous durations of time, and contain multiple decisions within them.

Example Workflow from Hamburg Participant #2

We observed that workflows appear to be naturally constructed actions to participants. Their workflows were so unconscious or self-evident, that participants often found it challenging to articulate and reconstruct their workflows. Examples of workflows include: Comparison shopping, checking email, checking news updates, and sharing an image with someone else.

Workflows Model

Based on our study, we have developed a general two-part model to illustrate a workflow.

Part 1: Workflows are constructed from discrete steps. These steps are atomic and include actions like typing in a URL, pressing a button, taking a screenshot, sending a text message, saving a bookmark, etc. We mean “atomic” in the sense that the steps are simple, irreducible actions in the browser or other software tools. When employed alone, these actions can achieve a simple result (e.g. creating a bookmark). Users build up the atomic actions into larger actions that constitute a workflow.

Part 2: Outside factors can influence the choices users make for both a whole workflow or steps within a workflow. These factors include software components, physical components, and pyscho/social/cultural factors.

Trying to find the Mozilla Berlin office.

While workflows are composed from atomic building blocks of tools, there is a great deal more that influences their construction and adoption among users.

Software Components

Software components are features of the operating system, the browser, and the specs of web technology that allow users to complete small atomic tasks. Some software components also constrain users into limited tasks or are obstacles to some workflows.

The basic building blocks of the browser are the features, tools, and preferences that allow users to complete tasks with the browser. Some examples include: Tabs, bookmarks, screenshots, authentication, and notifications.

Physical Components

Physical components are the devices and technology infrastructure that inform how users interact with software and the Internet. These components employ software but it is users’ physical interaction with them that makes these factors distinct. Some examples include: Access to the internet, network availability, and device form factors.

Psycho/Social/Cultural Factors

Psycho/Social/Cultural influences are contextual, social, and cognitive factors that affect users’ approaches to and decisions about their workflows.

Memory

Participants use memory to fill in gaps in their workflows where technology does not support persistence. For example, when comparison shopping, a user has multiple tabs open to compare prices; the user is using memory to keep in mind prices from the other tabs for the same item.

Control

Participants exercised control over the role of technology in their lives either actively or passively. For example, some participant believed that they received too many notifications from apps and services, and often did not understand how to change these settings. This experience eroded their sense of control over their technology and forced these participants to develop alternate strategies for regaining control over these interruptions. For others, notifications were seen as a benefit. For example, one of our Leipzig participants used home automation tools and their associated notifications on his mobile devices to give him more control over his home environment.

Other examples of psycho/social/cultural factors we observed included: Work/personal divides, identity management, fashion trends in technology adoption, and privacy concerns.

Using the Workflows Model

When analyzing current user workflows, the parts of the model should be cues to examine how the workflow is constructed and what factors influence its construction. When building new features, it can be helpful to ask the following questions to determine viability:

Hamburg Train Station

The Firefox User Research team conducted additional phases of this research in Canada, the United States, Japan, and Vietnam. Check back for updates on our work.

References:

¹ Pace, S. (2004). A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users. International journal of human-computer studies, 60(3), 327–363.

I was recently invited to the UIC Daley Library to speak to an awesome group of librarians that are using UX methods to learn about and improve their institutions. The workshop focused on my work at Mozilla, how to plan a research study, and best practices for user interviews. Activities throughout the day gave all the attendees hands-on experience scoping, drafting, and running a user interview. You can see my slides below and learn more about the Chicago Library UX group on their meetup page.

(© 2015 Gemma Petrie. All rights reserved.)

For many consumers, software and hardware choices are increasingly becoming choices between incompatible brand ecosystems. In today’s marketplace, a consumer’s smartphone choice is likely to have a far-reaching influence on options for everything from file storage to wearable technology. With each app purchase or third-party service sign-up, consumers become further invested in a closed brand ecosystem. As start-ups are acquired or privacy standards change, consumers may become trapped in an ecosystem that no longer meets their needs.

Mozilla strives to create competitive products and services built with open source technologies, that protect users from vendor lock-in, and that address user needs. We believe supporting these values is not only good for consumers, but is also good for our industry. In February, we conducted a contextual user research study on multi-device task continuity. This user research will help Mozilla design current and future products and services to support users’ behaviors and mental models. This research builds on our our Save, Share, Revisit study conducted earlier this year.

The Mozilla User Research team conducted three weeks of fieldwork in four cities: Columbus, OH; Las Vegas, NV; Nashville, TN; Rochester, NY. We recruited a demographically diverse group of 16 participants. Each participant invited members of their household to participate in the research, giving us 43 total participants between the ages of 7 and 52. All 16 interviews took place in the participants' homes. In addition to our primary research questions, the semi-structured interviews explored daily life, devices, and integration points. Further, participants provided home tours and engaged in multi-device workflow future thinking exercises.

If you are reading this blog post, there is probably a good chance that you work in the tech or design industry. You likely have fairly advanced technology usage compared to the average person in the United States. Your personal device and service ecosystem might look something like this:

The device and service ecosystem for the average person in the United States includes fewer elements and fewer connection points. For example, here is the ecosystem map of one of the 16 participant groups in our study:

As you can see in these diagrams, the average user has single points of connection between his primary device (MacBook Pro) and all the other devices and services he uses. The advanced user, on the other hand, is utilizing various tools to move content between multiple devices, contexts, and services.

Based on our research, we developed a general model of what the task continuity process looks like for our participants. Task continuity is a behavior cycle with three distinct stages: Discover, Hold/Push, and Recover.

The Discover stage of the task continuity cycle includes tasks or content in an evaluative state. At this stage, the user decides whether or not to (actively or passively) do something with the content.

The Hold/Push stage of the cycle describes the task continuity-enabling action taken by the user. In this stage, users may:

The user may also set a reminder to return to the task/content at this stage (e.g. Set an alarm to call the salon when they open). It is possible for a single action to bridge more than one Hold/Push state (e.g. Re-pinning content on Pinterest shares it with followers and saves it to a board). It is also possible that a user will take multiple actions on the same task/content (e.g. Emailing a news article to myself and a friend).

In the Recover stage of the task continuity cycle, the user is reminded of the task/content (e.g. By seeing an open tab) or recalls the task/content (e.g. Through contextual cues). Relying on memory was one of the most common recovery methods we observed. In order to fully recover the task/content, the user may need to perform additional actions like following a link or reconstructing an activity path.

Once the task/content is recovered, the user is able to continue the task in the Resume stage. Here, the user is able to complete the task or postpone it by re-entering the task continuity cycle.

The Task Continuity Model allows us to clearly map the steps involved in a specific task continuity activity. To illustrate, one of our participants discovered a video that he wanted to watch at a different time and on a different device. Here are the actions he performed to achieve this:

A selection of our research findings that we believe are the most relevant to UX professionals and engineers:

This research provided a valuable foundation and framework for our understanding of task continuity, but it is important to acknowledge that it was conducted only in the United States. We were particularly surprised by the reliance on texting and screenshots and believe it is important to explore this behavior in areas where carrier-based SMS programs are less popular. We plan to build upon these findings by expanding this research program to Asia in May 2015.

References:

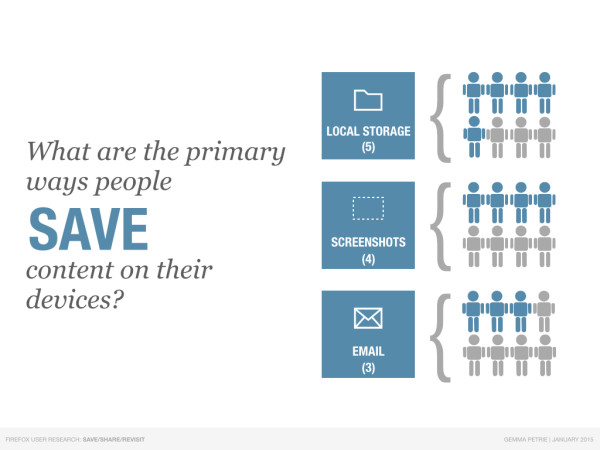

In early January, Mozilla conducted user research to refresh our understanding of how people save, share, and revisit content with the goal of building our knowledge base for a larger contextual research project on multi-device task continuity that is currently being conducted. (More on that in a future blog post.)

We recruited eight participants to engage in a three-day diary study to document their save, share, and revisiting behavior. Instructions were emailed to participants each morning based on daily themes: Saving, Sharing, Retrieving. Each evening, the participants were prompted to submit their diary entries and answer a few additional questions. Based on these responses, half of the participants were selected to participate in an additional 60-minute video interview with the researcher to explore these themes in greater detail.

People tend to save content to their devices, rather than to third-party systems. Some of the participants had tried services like Dropbox or iCloud, but abandoned them when they ran out of free storage space. Utilizing free local storage means people always know where to find things. If saving locally isn't possible, people will often take a screenshot of the content or send it to their own email account in order to save it.

“If there's a way I can physically save the article I would save it to my device or SIM card. If I can’t do that, I will take a screenshot of the articles and later go back and view them” - P6

“I found a picture of a toy I want to buy my daughter. I took a screenshot on my phone and I will go to the link in the pic using my computer later to show my mom.” -P2

For most participants, alternate device access was not a big concern when saving content. In fact, most of the time, people intended to revisit on the same device. When saving content, most people intended to revisit it within a short time frame - usually the same day or within a few days. This was due to the fact that people believed they would "forget" to return to the content if too much time passed.

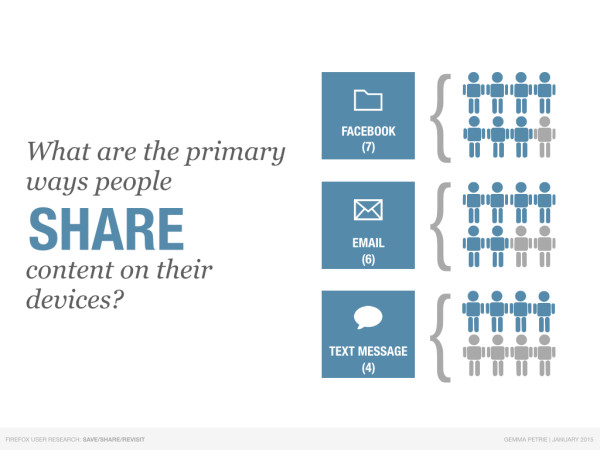

For many participants, the line between sharing and saving was blurred. The primary methods for sharing content - Facebook, email, and text messages - where valued not only because they made it easy to share, but because they also made it easy to revisit.

“Social media and email services make it easy to revisit content because they log and save everything.” - P3

“I found Crockpot recipes on Facebook that I wanted to try, so I re-posted it to my Facebook wall.” - P7

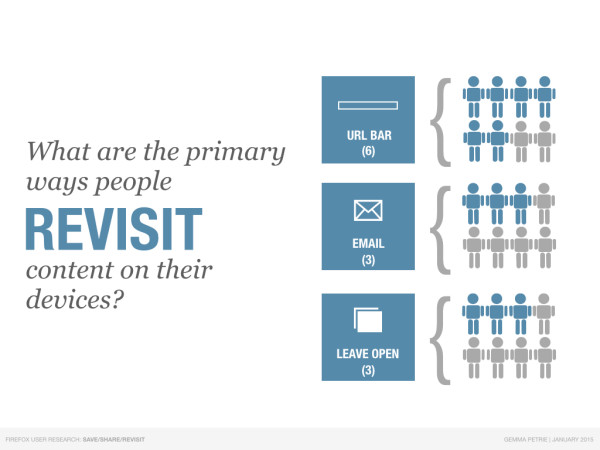

Participants used a variety of low-tech methods to revisit content. The primary methods included relying on the URL bar to autocomplete URLS based on browser history, following links in emails, and leaving browser windows open.

The Firefox UX research team is currently conducting a contextual user research project in multiple cities to learn more about multi-device task continuity strategies. These findings will add depth to our current understanding and help us design experiences that will support and expand on these user patterns. Stay tuned for more information on this work.

(You can find the original post on the Mozilla UX Blog.)

This research was led by Cori Schauer & Gemma Petrie.

Last month, Mozilla traveled to India to conduct user research on mobile usage. We are grateful to our talented research partners Dear and Tazurba International for their expert local knowledge, to the amazing Delhi and Rajasthani Mozilla communities who provided critical logistics and translation support, and to the many Mozilla staff members that took time out of their busy personal and professional lives to join us in the beautiful (and blazing hot!) Indian summer.

The Mozilla User Research team believes it is important to bring a wide variety of colleagues into the field with us for research. We know that first-hand experience does more to build empathy and understanding than a presentation ever will. This trip marked our largest field team to date and included:

We aimed to answer the following questions with our research:

India is a vast and varied country and it was difficult to design a research approach that would cover multiple regions with adequate depth in the time we had available. We decided early on to focus this initial phase of our India research program in the north, specifically in Delhi, rural Rajasthan, and Jaipur.

This research used a variety of methodologies to gather data. We conducted one-on-one interviews in Delhi and Jaipur and worked with community members and local researchers to meet with local families, shopkeepers, and visit rural villages. In addition, we also conducted informal ethnographic observation during our two weeks in India.

One of our primary goals was to immerse our field team in Indian daily life and culture. Our large group and broad geographic research area presented some initial challenges during our planning stage. We made the decision to engage dscout to bring some order to our data collection and help field team members that were new to research think about how to capture and analyze their experiences.

We split each day into two modules with different themes like phone stores, mobile content, or family. We then divided our field team into small groups, accompanied by Mozilla community members, to explore different areas. Each group added photos, videos, and answers to a few short questions to dscout, allowing us to quickly gather a large amount of structured information on each theme. This data, combined with our team's first-hand field experiences, provided a valuable contextual foundation for our research.

We conducted one-on-one interviews with 55 recruited participants at "Open House" events in Delhi and Jaipur. The interviews were split into four main topic areas: Current phone and technology usage, phone purchasing process, mobile content, and Firefox OS device user testing.

This research was led by Bill Selman & Gemma Petrie.

In Fall 2013, the Mozilla User Experience Research Team visited Thailand and Indonesia to conduct Firefox qualitative research. In addition to our team of Mozillians, we partnered with SonicRim, a global design research firm, on this research project. If you would like to learn more about the project planning phase of this study, please read the first post in this series. You can also read about our initial observations in Thailand and our initial observations in Indonesia in previous posts. Finally, you can also checkout this follow-up post on ecommerce in Indonesia.

The goal of this research project was to understand how people in Thailand and Indonesia experience the Internet and to learn about emerging trends that will provide insight into new and current product features for Firefox.

The Mozilla User Research team believes it is important to experience in-context research with a wide variety of staff members. We brought a diverse set of talents into the field with us and gave each person the opportunity to engage in cultural immersion activities and two or more qualitative interviews in Bangkok & Chiang Mai, Thailand or Jakarta & Bandung, Indonesia. Our field teams were comprised of: Bill Selman (User Research), Gemma Petrie (User Research), Uday Dandavate (SonicRim Researcher), Larissa Co (UX Design), Zhenshuo Fang (UX Design), Holly Habstritt (UX Design), Bram Pitoyo (UX Design), Margaret Schroeder (Market Research), Gavin Sharp (Firefox Engineering), and Yuan Wang (UX Design).

We engaged in a variety of contextual inquiry and ethnographic research activities including:

In Indonesia and Thailand, changes are taking place with respect to how (and how many) people are accessing the Internet. Rapid technological and socioeconomic development has influenced technology adoption curves and technology-centric behaviors. Our research identified various themes that will help inform the future development of our products. Here are a few of them:

Key pieces of critical infrastructure are lagging, especially in Indonesia.1-5

This lack of stable infrastructure inhibits what can be done with technology and influences software adoption and software updates due to poor or nonexistent download speeds.

Due to poor connectivity, downloading is often not the only software distribution channel in this region. Physical media such as DVDs and USB thumb drives still play a significant role in how software is distributed and installed. As a result, software packages are frequently installed in a shop, rather than at home. These packages can include everything from the OS, to multiple browsers, productivity tools, and games. In Indonesia, software being sold is often several versions behind the current version and may be compromised with malware.

Participants have difficulty searching the Internet, because they don’t understand the pieces of the browser and the relationship of the browser to the Internet. This resulted in several beliefs:

Internet users in both markets rely on a blend of English and local language sources in order to find information they need. Users often, but not always, use English language menus on their devices (especially among Thai users trying to save screen real estate). Yet, while many users can navigate effectively in English, translation is still critical to their browsing experience. People want content in a context appropriate language: Local content in the local language and international content In English. Overall, there was a distrust of machine translations and a desire for improved content translation that provided additional cultural context.

Mozilla is committed to providing the best user experience possible to our global community of users. It is important for us to understand the unique challenges and unmet needs that our users face around the world. We are grateful to all of the participants we were able to interview during this project and to the valuable support of our Thai and Indonesian communities. Over the last few months, our research team shared all of our Thailand and Indonesia study results with various teams at Mozilla. In addition to our observations, we suggested opportunities for addressing the unmet needs in this region. We look forward to incorporating design solutions to these challenges in our products. Stay tuned!

References:

Build. Empower. Teach. Shape. When Mitchell Baker defined the Nature of Mozilla in her keynote at this year's Mozilla Summit, she highlighted these activities to be our main responsibilities as Mozillians.

The User Research team is dedicated to understanding who our users are and how to build products that will meet their needs. Earlier this year we completed the Firefox User Types study as part of this effort. This research has already been used by internal Mozilla teams to think about different features and design solutions for Firefox, and the Summit gave the User Research team the opportunity to share this work with the entire Mozillia community. Our session, "Designing for our users, not for ourselves," was facilitated by Mozilla User Research team members in all three Summit locations: Toronto (Cori Schauer & Gregg Lind), Santa Clara (Bill Selman & Lindsay Kenzig), and Brussels (Gemma Petrie and Dominik Strohmeier). Special thanks to our amazing UR and UX colleagues for their support at each session!

The summit was an awesome experience with more than 1,800 Mozillians across three locations. We were excited to share our work during our UR/UX breakout sessions, but with so many concurrent tracks, we knew not everyone would be able to to attend. In order to convey our enthusiasm for our research, spread the word about our sessions, and get the community talking about who our users are, we created and distributed enamel user type pins to all of the Mozillians in attendance.

The pins were a hit and within minutes the keynote auditorium was full of Mozillians trying to trade with one another for their favorite user type. Nearly half of our community members fall into the "Wizard" category of users, but in our research this user type only represents 1% of North American Firefox users. We deliberately distributed only a few "Wizard" pins at the Summit in order to get people talking, and did it ever! As people frantically searched for these elusive pins, it gave us the opportunity to discuss the theme of our talk, "Designing for our users, not for ourselves." (Thanks to Zhenshuo Fang for her lovely user types artwork and to Madhava Enros for the pin idea!)

The word was out about User Types, and more than 60 Mozillians came to the session in Brussels, 35 in Toronto and 30 in Santa Clara to learn more. During the presentation, we introduced everybody to the concept of having user types to guide our design and product development process. We also introduced each of the user types and their specific characteristics. We then split the room into six groups and each group received a short user profile, a collection of photos, pens, paper, and two exercises:

After finishing the exercises, each group presented their results to the other teams. The goal of our session was to make people start thinking like one of our user types and we were incredibly impressed with the thoughtful ideas each group shared. The presentations highlighted an important constraint our designers work with every day: There are very different ideas about the Web and what Firefox could offer each of the user types, however we only develop one Firefox Desktop which needs to serve all of our users.

Thanks to all the Mozillians in the different Summit locations who joined our session. In Brussels, we especially enjoyed the long discussion that followed after the official session ended. We hope that these discussions will continue and that we will all keep the user types in mind when working on future products so that we are better able to build the Internet the world needs. (Special thanks to Cori Schauer for her work preparing this session!)

In August and September, the Mozilla User Experience Research Team visited Thailand and Indonesia to conduct Firefox qualitative research. The goal of this research project was to understand how people in these markets experience the Internet and to learn about emerging trends that will provide insight into new and current product features. If you would like to learn more about the project planning phase of this study, please read the first post in this series. The fieldwork teams will be dedicating the end of September to the thorough analysis of our findings. In the meantime, we are excited to share five initial observations from our Thailand fieldwork.

The Mozilla research team, along with our partner SonicRim, interviewed 22 participants in 11 sessions over a two week period in Bangkok and Chiang Mai, Thailand. We also had the opportunity to explore cultural sights, public transportation, new and second-hand electronics stores, public spaces, Internet cafes, and universities.

The transportation options in Thai cities are seemingly endless - everything from motor bikes and tuk tuks for hire to public boats and trains. In Bangkok, the congestion is also seemingly endless, with an average road speed of less than 10 mph.Perhaps as a result of these long commutes, mobile devices are popular and prevalent on all types of transportation. In fact, Thailand has a mobile phone penetration rate of 120%, which means there are more mobile phones in use than there are people.

While basic feature phones are still the most common mobile device in Thailand, smartphone sales have more than doubled in the last two years.3 The latest high-end phones (Samsung, Apple, Nexus) are very popular, though cheaper models, used devices, and knock-offs are also abundant. Mobile phones are routinely sold unlocked in Thailand, which makes it easier to sell used devices or upgrade to the latest technology.

The Thai government has committed 30 billion baht (US$0.94 billion) to its "Smart Thailand" initiative in an effort to connect 85% of the country to high-speed broadband by 2015.4 The government has also partnered with major telecom providers to install more than 120,000 free wifi access points in Bangkok.5 And in May of this year, 20 Thai provinces received the nation's first true 3G service.6 Yet, even with this huge investment in infrastructure, connection speed, price, and availability continued to be major issues for the Thai people we interviewed.

Unlicensed software bundles are prevalent in both ad-hoc mall kiosks and more formal stores. As a result, most people have the latest OS and software. It is common for people to buy computers with no operating system installed and buy a package of basic, unlicensed software directly from the salesperson. A typical package included Windows 7, MS Office, Adobe CS 5, antivirus, YouTube Downloader, and multiple browsers (Chrome, Firefox, and IE) for 600 baht (US$20). In contrast, a licensed copy of Windows 8 would cost the consumer 5000 baht (US$130). Similarly, unlicensed smartphone app bundles were also available.

Our research indicates that Thai people are more concerned with ease of use, familiarity, and personal recommendations when it comes to technology than they are with brand loyalty. When asked why they were using a particular piece of software, the overwhelming majority said it had been recommended and installed by the person who sold them their device, or it had been recommended by a friend or family member. Personal research or brand recognition did not appear to be factors for most Thai consumers.

Next in this series: The Internet and Browsing in Indonesia: Five Findings from the Field

References:

Every good UX researcher has the ability to become totally engrossed in even the smallest research project. Yet, one of the amazing things about working for a global, mission-driven organization like Mozilla is the opportunity to take on some truly big research challenges. The Mozilla UX Research team is about to embark on such a project as we begin our Firefox Southeast Asia research in Thailand and Indonesia.

The primary goal of this research project is to understand how people in specific emerging markets experience the Internet and learn about emerging trends that will provide insight into new and current product features. We are particularly interested in learning about the context of Internet use, values related to the Internet, and specific Internet usage.

So, why not just send out a few surveys? Mozilla believes that there are valuable insights that can only be generated by in-context, ethnographic research. We recognize that many of the people involved in creating new technologies live in a fairly limited tech bubble and we truly value learning from a global community of Internet users.

One of the more challenging decisions researchers have to make at the beginning of a project is how to appropriately limit the scope of the research question. For this project, we have decided to focus on Thailand, Indonesia, and India. (India is slated for early 2014.) Both Thailand and Indonesia have rapidly growing economies and relatively low internet penetration rates. Interestingly, the Firefox market share in these two countries is dramatically different. Firefox holds 64% of the browser market in Indonesia, yet only accounts for 23% of the market in Thailand. We believe these two countries will provide valuable insight into understanding user needs and improving the Firefox market share.

A small team of user experience, engineering, and marketing Mozillians will be traveling to Thailand and Indonesia to conduct user interviews and ethnographic research in August and September. We have partnered with SonicRim, an awesome global design research firm, on this research project. Our research is divided into three phases: Planning & Recruiting, Fieldwork, and Analysis.

I said goodbye to my friends at Razorfish earlier this summer to accept an amazing opportunity to join the Mozilla User Experience team as a User Experience Researcher. I'm looking forward to working for a mission-driven organization where I am able to publicly discuss my work!